Take a look at the course offerings of most top-tier business schools and you’ll find listings like “Applied Business Forecasting,” where students “acquire hands-on experience with building and applying forecasting models to actual data on sales, inventories, income, earnings per share, and other variables widely encountered in business, to take an example from the University of Michigan Ross School of Business.

Take a look at the course offerings of most top-tier business schools and you’ll find listings like “Applied Business Forecasting,” where students “acquire hands-on experience with building and applying forecasting models to actual data on sales, inventories, income, earnings per share, and other variables widely encountered in business, to take an example from the University of Michigan Ross School of Business.

Forecasting sales isn’t just taught in the halls of academia — it’s a standard part of business plans and real-world management. And it isn’t done in the high/medium/low terms common in risk management, either. From simple formulas (unit sales x profit per unit = forecasted profit) to the most complex, sales forecasting is done using numbers.

If the business world is so comfortable quantitatively forecasting positive outcomes, why is the practice of quantitatively forecasting negative outcomes facing such headwinds to widespread adoption?

First, we’ve allowed the flawed “probability/likelihood x impact = risk” model to hold sway in our industry for too long.

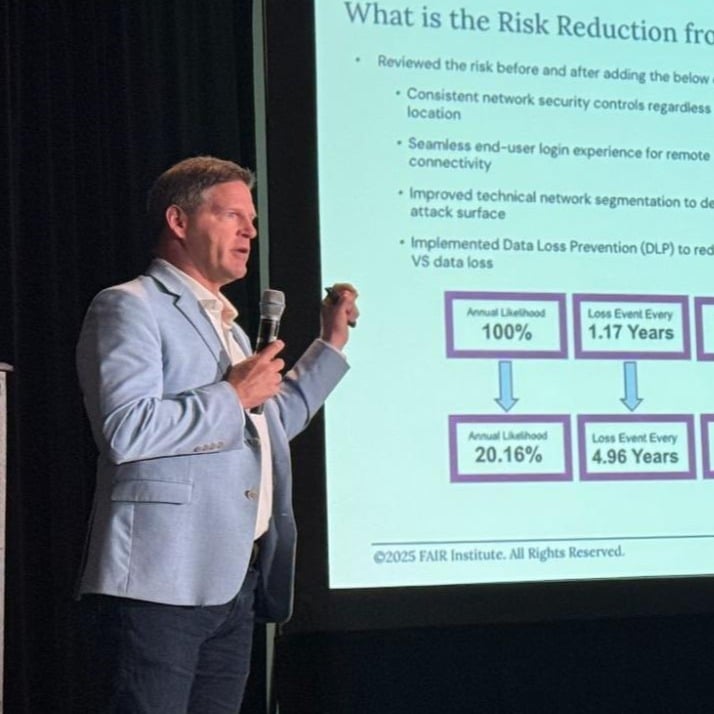

Quantifying risk exposure involves understanding how many times a bad thing will happen over a given timeframe — frequency, not probability or likelihood — and how much money the organization will lose each time it does. This is analogous to the simple sales forecasting model stated above:

number of loss events x loss per event = forecasted loss

number of units sold x profit per unit = forecasted profit

Second, we’ve somehow convinced ourselves that it’s okay to talk about dollars of future loss, a quantity, in meaningless qualitative terms.

Imagine presenting a CEO with a report that says, “the number of units we think we’ll sell is rated as medium, the profit per unit is rated as high, therefore our forecasted profit is rated as high.” You would get laughed out of the building, and rightfully so! Talking about quantities using subjectively-interpreted qualitative labels hinders effective decision-making — should the company move forward with the launch of this product based on its high forecasted profit rating? It’s ludicrous to think that any organization makes resource allocation decisions this way, yet we’ve grown to accept it in risk management.

Instead, let’s use numbers to talk about things that are quantities — imagine that! Just like making an estimate of the number of units sold, you can make an estimate of the number of times a given loss event will occur. In both cases you’re going to refer to the best data you can find and talk to subject matter experts to inform your estimate.

While we may be working with less readily available data when forecasting loss than when we’re forecasting sales, the basic structure is the same. Your organization has to embrace quantitatively forecasting loss to the same extent as you quantitatively forecast sales, revenue, or profits if you want to most effectively use your limited resources to increase the organization’s value.

Fight your fear of forecasting losses by:

- Realizing that you’re already comfortable making forecasts accounting for uncertainty in other realms and that forecasting losses is no different.

- Updating your formula for forecasted losses: probability x impact doesn’t cut it. When we’re forecasting sales do we use the probability of making a sale or do we count the number of units sold? The same holds true for loss events; when forecasting risk, I care about how many times the loss event will happen — frequency — not probability.

- Embracing uncertainty. You will never have perfect information about how many times your organization will face a certain type of cyberattack (just as you never have perfect information about how many units you’ll sell), but you have enough information to make a reasonable estimate and significantly reduce uncertainty. When you’re asked, “how much risk do we have from scenario x?” you’ll never be able to provide a precise answer unless you have a crystal ball or mystical abilities. But what you can do is provide an accurate range based on the best available information.

FAIR (Factor Analysis of Information Risk) is the only internationally recognized standard for operational and cyber risk quantification. Gartner, the influential technology consulting firm, has named “risk quantification and analytics” to its “list of "critical capabilities" for integrated risk management (IRM). To learn more about FAIR and risk quantification, join the 3,000 risk professionals who are members of the FAIR Institute.