The idea of the “criticality” of an asset or resource appears in many cyber security standards, including NIST, ISO 27001, and the AICPA’s SSAE 16 criteria.

The idea of the “criticality” of an asset or resource appears in many cyber security standards, including NIST, ISO 27001, and the AICPA’s SSAE 16 criteria.

Of the standards that define criticality, the best is in NIST SP800-53r4: “A measure of the degree to which an organization depends on the information or information system for the success of a mission or business function.”

This article proposes an interpretation of the NIST definition that makes criticality quantitative and measurable, and potentially amenable to being incorporated into the FAIR model.

It’s a definition that can remove much of the subjectivity of another NIST definition of criticality, “a measure of the importance assigned to information by its owner for the purpose of denoting its need for protection.” (SP800-30r1, emphasis added)

Mission Capability

The first step is to generalize the definition to apply to any resource that is important to the organization’s ability to achieve its mission. It could be information or an information system, a business process, intellectual property, or something on the firm’s asset ledger. In this context we’ll just call it an asset.

The idea of criticality of an asset hinges on how important it is to the organization’s ability to accomplish its mission. During normal times the organization has some overall ability to accomplish its main mission or missions. But during recovery from a particular loss event, is the organization able to accomplish its mission, or not? Or more generally what is likelihood that the organization can or will be able to accomplish its mission? This reasoning leads us to the following definition:

Mission Capability is the probability, when the organization is in a given situation, that the organization can accomplish a core mission.

Mission capability varies depending on the loss situation. A company’s mission capability is reduced if it has lost use of 10% of its assets due to a cyber breach – or anything else. A government agency’s mission capability is reduced if its budget is cut or its political influence is reduced. A military unit’s mission capability is reduced if it has sustained losses of personnel and equipment.

Since every organization has a mission, the idea of mission capability is quite general. For the definition of mission capability to be operationally useful, it must be possible for its leaders or stakeholders to clearly determine whether a mission has been, or could be, accomplished. If not, the organization has other troubles!

Criticality

We can now reconsider criticality. Intuitively, an asset is critical to an organization if not having it significantly impairs its mission capability. Therefore the criticality of an asset is the degree to which unexpectedly not having it reduces mission capability. To “have it” means that the asset is available for use, in the quantity and with the quality normally expected, at the time of expected need. If a manufacturing line is down for scheduled maintenance, it is not unavailable for the mission since maintenance is in the plan. This leads us finally to an improved definition of criticality:

The Criticality of an asset is the amount by which the mission capability of the organization is reduced when the asset is not available as expected.

So criticality is the difference of two probabilities, the probability of achieving the mission when the asset is available as expected, and when it is not.

|

Criticality of Asset A = Mission Capability when A is available - Mission Capability when A is not available In other words, Criticality of Asset = Probability (mission accomplished / asset available) - Probability (mission accomplished / asset not available) |

Therefore criticality ranges between zero and one, or 0% and 100%. The idea can be extended to an asset being only partially available, i.e. not up to par. “Sorry, captain, I cannae give ye warp 9. She just cannae take it.”

Relationship to FAIR

FAIR does not currently have the notion of mission capability. But the gap is not wide.

First, the FAIR standard assumes that the value of any asset can be expressed in money, but this does not limit its use. You can just as well imagine a FAIR analysis where the units of loss magnitude are units of blood, lives, or disease-free days. Using non-monetary units of loss can mollify critics who deny that everything can or should be reduced to money.

Second, any asset that the organization has should have some bearing on mission capability. If not, why have it?

Third, the FAIR ontology officially has only a single dimension of loss, money. For various reasons including politics and palatability of the analysis to stakeholders, multiple dimensions may be needed. Hospitals must consider loss of life and hospital-acquired illness, among many examples easy to imagine.

The structure of the FAIR ontology applies to each dimension. Multi-attribute utility theory or a future evolution of FAIR could model how losses for multiple asset types impact mission capability. Cross-dependencies among asset risks could be important, which is one thing that makes executive decision making hard. If a hospital changes its care model to reduce acquired illnesses, costs could increase.

When analyzing risk to one asset at a time, the risk analyst needs to model how mission capability depends on the amount of that asset that is available, given a particular scenario and loss event type.

The result will be mission capability as a function of the loss magnitude. When multiplied by the probability of loss magnitude from the FAIR analysis, the result is a single number, expected mission capability, which directly gives criticality by subtraction.

Time for an Example

Let’s suppose that a certain executive of a candy company has her bonus (if not continued employment) tied to ability of the Jupiter bar production line meeting its production goal. That line is connected electronically to a key supplier, and she is concerned that a malware attack coming over that connection could bring down the line. That is the scenario she has asked to be analyzed for risk.

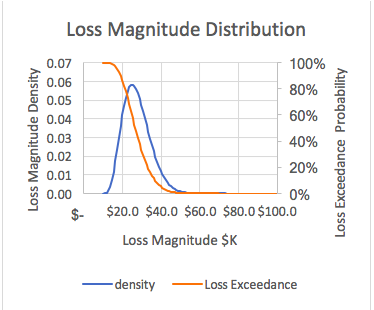

The risk analyst consults production experts and historical records to come up with the following estimates for potential losses.

|

Minimum possible loss if a breach occurs |

$10K |

|

Most likely loss |

$25K |

|

Maximum conceivable loss |

$100K |

|

95% confidence level of loss |

$40K |

The executive agrees with these estimates. The risk analyst decides that a reasonable model of these loss characteristics is a PERT distribution, which when graphed out looks like this. (This could have come from a FAIR analysis of threats against the asset.)

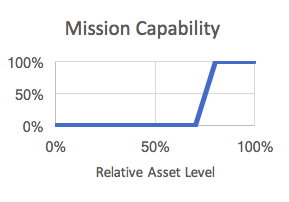

By interviewing the executive and some of her advisors, the risk analyst determines that a reasonable model of mission capability is this:

- If losses are less than $20K, the production goal can still be met, so mission capability is 100%. (We could say that the line is “resilient” to $20K of loss.)

- On the other hand, if losses are greater than $30K, the production goal cannot be met, so mission capability is 0%.

- In between, mission capability falls proportionally to the asset loss magnitude.

Graphically the way mission capability depends on the amount of surviving assets (as a percentage of $100K) looks like this.

The mission capability in the given loss scenario is expressed as:

|

Mission Capability = Probability that the mission will be accomplished = ∑x (mission capability if loss magnitude = x) x (Probability that loss magnitude = x) |

With some spreadsheet mechanics, the risk analyst finds that, given these estimates and assumptions, the overall probability that the mission will be accomplished if a loss event occurs is about 40%.

Since the executive believes that the production goal (mission) will be accomplished with a likelihood of 98% if there is no loss event, the criticality of this asset is the difference between 98% and 40%, or 58%. That’s how much the mission capability falls if the Jupiter line is not available as expected.

The analysis confirms the executive’s intuition that availability of the Jupiter line is critical to her meeting the production goal and getting her bonus. She also realizes that she now knows the criticality of the asset whether the loss event is a cyber security breach or anything else.

Criticality Is about Mission, Not Threat

In this analysis we have assumed a data breach to fix ideas and get to the criticality of the asset. But the analysis did not use anything about a data breach or any other kind of a threat event. This is because the idea of criticality is how important an asset is to the mission, and not about how sensitively the availability of the asset may depend on what kind of a loss event may occur, or for that matter on the threat type, threat community, the capability of the threat actor, or the effectiveness of controls. The whole idea is to see how loss magnitude connects to mission.