Leveraging the Human Element for a Successful FAIR Risk Management Program, Part 2

We are back with the next installment of blog posts meant to explore four frictions acting against our innovative ideas when building risk programs with the objective of improving the pace and quality of decision making within our organizations. A quick recap might cue your memory and bring this topic back to the top of your mind, so here are the primary points we covered in Part 1:

We are back with the next installment of blog posts meant to explore four frictions acting against our innovative ideas when building risk programs with the objective of improving the pace and quality of decision making within our organizations. A quick recap might cue your memory and bring this topic back to the top of your mind, so here are the primary points we covered in Part 1:

- We wear a lot of hats as we’re building and managing risk programs. We’re forecasters, change managers, evangelists, and even scientists at times.

- It takes someone who is curious, progressive, disruptive, and innovative to increase the appeal of a novel and unfamiliar idea and influence an organization to embrace the change needed to adopt it.

- Thinking in fuel, or highlighting the appeal, benefits, and value of an idea is vital to success and is the driving force providing the energy needed to propel our great ideas forward. We inherently prioritize adding fuel, and often de-prioritize addressing friction, because we falsely attribute a lack of desired behavior with our own failure to prompt enough optimism and enthusiasm for our initiative.

- It’s the friction, however, generated by fuel, that impedes our ability to embrace innovation and it’s a losing gamble to underestimate the headwinds this creates against the new ideas we promote.

- Inertia is a powerful source of friction, enticing us to stick with the present situation and show reluctance to drift too far from what’s familiar. It’s a product of our evolutionary biology and hard-wired in human nature, making it difficult to alleviate but necessary to manage to help overcome our deeply rooted resistance to change.

Author Zach Cossairt is Integrated Risk Program Senior Manager at Equinix and winner of the FAIR Business Innovator Award for 2021. Learn more about Zach.

Author Zach Cossairt is Integrated Risk Program Senior Manager at Equinix and winner of the FAIR Business Innovator Award for 2021. Learn more about Zach.

Hear Zach speak at the 2023 FAIR Conference, Tuesday, October 17, on “The CRQ Program Development Lifecycle.” Get conference information now.

This post will navigate the second of four frictions described in Loran Nordgren and David Schonthal’s book The Human Element that may be hindering the positive transformations we attempt to produce as we architect, manage, and scale our quantitative risk programs. I’ll share my perspective on why this friction exists and suggest practical strategies to apply behavioral insights in a solution-focused approach to assist with managing the organizational change needed to progress and adopt innovative ways of managing risk.

Part 2 of Leveraging the Human Element

Effort: Prioritizing the Path of Least Resistance

There is an ancient law influencing our preference to seek out the path that provides the largest reward for the least amount of effort. This law of least effort is instinctual and possibly the most robust psychological force acting against our decisions. Our inclination to take the easier route is so deeply embedded even, that it has been shown we perceive simpler options as more appealing.

These points have implications for us as we engineer behavior change because the risk management alternative we are offering is not the only one that our stakeholders have to choose from. Those who contemplate utilizing our services economize effort as a cost and weigh it against perceived benefits to decide if the option we are presenting will provide enough reward to outweigh the opportunity cost of doing something else.

With the understanding that humans are motivated to do what is easy and predisposed to work toward results that require the least amount of work to achieve, let’s explore how we can use this information to shift the effort calculation in our favor and encourage adoption of our innovative idea.

A Risk Management as a Service Approach

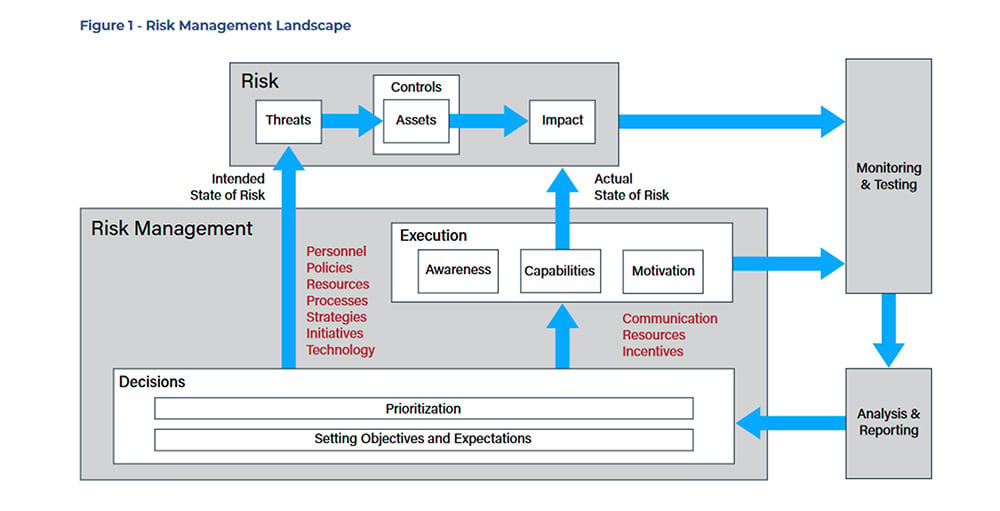

This year, Gartner identified human-centric security design that prioritizes the role of employee experience as the number one cybersecurity trend for 2023. I believe that the shift in focus Gartner recommends to security leaders applies not only to the capabilities in which they invest to mitigate cybersecurity risks, but also to the services that are implemented to manage the risk landscape itself. To illustrate this point, look at the figure below from Jack Jones’ Understanding Cyber Risk Quantification: A Buyers Guide and while doing so, evaluate the various action-oriented decision points that exist within the risk landscape we are tasked with managing.

The services put in place to successfully manage this environment would benefit from undertaking a design process to develop a context facilitating action by the humans interacting within the landscape. Thinking about managing risk this way aligns with Gartner’s guidance by moving past the familiar status quo of program management and rather offering a product to stakeholders that adds value by improving the pace and quality of their decision making. Encouraging the human actions needed to make this work requires us to be good choice architects that apply principles of behavioral design echoing the following anthem touted by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein in their book Nudge.

Make It Easy.

The following is a practical example with strategies that adopt this simple yet often underestimated mantra intended to help overcome the effort-based friction producing drag on our desired behavior. It is important to note that you can choose any behavior you wish to improve and apply the tactics that follow to reduce the friction present in the system.

Diagnose the Behavior

What actions must someone take in order to reach the target outcome you want them to achieve? If you haven’t gotten awkwardly specific with defining what someone needs to do, when, and how they should do it, then you likely don’t have a solid enough understanding of the level of effort involved with successfully carrying out the key behavior.

Let’s show an example from what many FAIR practitioners would probably note as one of the most human-centric aspects of risk assessment. Identifying a risk decision to support and scoping out the assessment.

Identifying a risk problem to solve: We’re in the business of solving dilemmas by reducing uncertainty creating risk for decisions, and making a decision is necessary in an undesirable current state where exploration is needed to evaluate options that may provide an improved output. Establishing a form of intake is generally a good idea to operationalize a mechanism for people to bring their issues and although we can see automation becoming mainstream in our field, the robots cannot (yet) determine a choice needs to be made in a complex environment overwhelmed with risk and uncertainty.

Hear Zach Cossairt speak at the 2023 FAIR Conference, Tuesday, October 17, on “The CRQ Program Development Lifecycle.” Get conference information now.

Defining the key behavior required to identify a risk problem to solve and engage in a scoping exercise might look something like this:

- A stakeholder will receive a link to a web page from the risk team and reach the intake form where they will be required to provide contextual information including the type of decision support they are requesting, the timeframe for a risk decision, an explanation of the issue or concern, the in-scope information assets, and the adverse effects that should be considered when assessing the risk.

- Once the intake form is submitted, the primary stakeholder will receive an email invite from a risk team member to participate in one or more calls to validate the context, relevant assets, threat agents, threat events, and loss effects within scope of the risk scenarios that will be analyzed. Additional stakeholders may be required to support this scoping engagement to provide useful data and information when decomposing each relevant loss scenarios from the primary stakeholder’s perspective.

Pretty specific, right? That’s the point. I’ll avoid lengthening this example to honor the theme of this blog post to make things easy, but I will add that visually mapping out the key behavior with attention to the details of each step can provide additional value when identifying and alleviating the barriers creating friction on the behavior we wish our stakeholders to achieve.

Assessing barriers in the system supporting each step in the key behavior allows us to understand what factors may be enabling, or inhibiting, the actions we need our stakeholders to take. Sticking with the example above, we can ask ourselves questions related to two primary dimensions of effort noted by Nordgren and Schonthal that create barriers influenced by heuristic principles and their associated cognitive biases.

- Ambiguity: Is it clear what the human who is expected to carry out the behavior needs to do to achieve their goal? Answering this question requires you to engage System 2 and perspective shift to objectively evaluate the action as someone who is not an experienced risk professional and does not have all of the answers. The message that is clear to us might be written in invisible ink to others, so it is necessary to help our stakeholders overcome the cognitive overload barrier making behaviors aversive and therefore more likely to be avoided.

- Exertion: How big are the hurdles someone needs to jump to reach their goal? Again, perspective shifting is important, and we can proactively identify the barriers and either remove them completely or create shortcuts by streamlining the behavior we want our users to achieve.

How to Practically Apply these Concepts:

Our authors Nordgren and Schonthal tell us that we can reduce the amount of time someone takes searching for the most optimal route by eliminating ambiguity and clearing the path for them. This can be achieved with useful help text for various fields a user must complete in a form to reduce their cognitive cost of exploration. Not everyone understands the difference between strategic and tactical decision support, the C-I-A triad, or even data types and classifications. Take this point seriously and design your choice systems accordingly.

An effort to streamline the behavior can include mapping out the steps a user has to take and even providing them with a few Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) and answers to the self-evident friction points you already know exist. Providing these shortcuts can improve users’ confidence when making choices and relieve the decision paralysis often plaguing those inclined to procrastinate and abandon long-term goals in favor of more immediate gratification.

Conclusion

Implementing a systems approach to managing the risk landscape can be assisted by disrupting the status quo of program building and rather supplying a product that aids the humans making choices within the risk management system. Although conceptually attractive, this change in mindset introduces an increasing and challenging consideration for human-centric design. The human mind favors the path of least resistance and when we encounter something new demanding our precious cognitive resources we will calculate the cost before deciding whether to act. This instinct to prioritize actions with favorable effort calculations is arguably the most powerful psychological force affecting our decisions and a friction that can easily weaken the appeal of a new and innovative idea.

This post has analyzed one practical example within the risk management system where we can design for behavior that obeys the law of least effort but these concepts can be applied anywhere change can be expected or an improvement in human behavior is desired. As risk professionals tasked with bringing innovation to our field, we are in the business of behavior change and the more we dedicate ourselves to work with human nature rather than against it, the faster we will observe better decision tools being utilized in a more widespread and meaningful way.

Hear Zach Cossairt speak at the 2023 FAIR Conference, Tuesday, October 17, on “The CRQ Program Development Lifecycle.” Get conference information now.

Read Part 1 of Zach’s series on Leveraging the Human Element.