The National Institute of Standards Cybersecurity Framework (NIST CSF for short) is a set of best practices recommended for businesses to protect critical IT infrastructure. Published in 2014, it’s been adopted by about one-third of large companies at least in part, as indicated by a survey of CISOs last year by Tenable Network Security.

The National Institute of Standards Cybersecurity Framework (NIST CSF for short) is a set of best practices recommended for businesses to protect critical IT infrastructure. Published in 2014, it’s been adopted by about one-third of large companies at least in part, as indicated by a survey of CISOs last year by Tenable Network Security.

Emphasis on “in part”—the Framework makes suggestions for compliance in 98 subcategories, a lot to tackle, without good guidance on prioritization. No wonder that the same survey found that only about 20% of companies rate themselves as “very mature” in working their way through the CSF checklist.

If your company is considering entering or expanding a NIST CSF compliance program, read this short guide to sharpen your thinking on the Framework, its uses, limitations and where it’s going.

What Does the Cybersecurity Framework Say?

You can read the original document; it’s not that long, and it’s clearly written: Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity

The key elements are:

- Framework Core

Focuses on five functions of cybersecurity risk management: Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, Recover.

Under each are categories and subcategories, for instance, Identify→Risk Assessment→Risk Responses Are Identified and Prioritized.

Each subcategory is paired with a list of standards (NIST, COBIT, ISO, etc.) to follow, with the expectation that companies will make their own choices on measurement scales.

- Framework Implementation Tiers

From “Tier 1 – Partial” to “Tier 4 – Adaptive”, a system with suggestions for companies to judge their level of competence in three areas: Risk Management Process, Integrated Risk Management Program and External Participation (coordinating with vendors or partners).

NIST says the Tiers are not meant to be a measurement scale for the subcategories.

- Framework Profile

Without giving detailed prescriptions, NIST wants companies to create a profile of themselves based on their business requirements, risk tolerance and available resources, as a guide to picking and choosing among the options suggested in the Core and Tiers.

The document goes on to suggest some ways that businesses could use the Framework to start or evaluate a cybersecurity program. “The Framework can also help an organization answer fundamental questions, including ‘How are we doing?’,” the document says.

Can the Framework Really Answer the Question "How Are We Doing on Cybersecurity?"

Read this series of blog posts by FAIR model author Jack Jones to gain a clear picture of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and limitations of NIST CSF.

Jack’s key points (in Parts 1 through 3 of the series) …

On the upside, the Framework has these strengths:

- Concise, efficient and adaptable.

- Comes at cybersecurity from the point of view of risks rather than just suggesting controls to implement.

- The Tiers with their multilevel measurement are an improvement over the usual yes/no approach to cybersecurity evaluation.

But the Framework is still basically a compliance checklist and therefore has these weaknesses:

- By complying, organizations are assumed to have less risk. But the Framework doesn’t help to measure risk.

- The Framework can show directional improvement, from Tier 1 to Tier 2, for instance but can’t show the ROI of improvement.

- Without reporting on risk level, there’s no guidance for companies on where they should be on the scale: Tier 2? Tier 3?

The net result, Jack Jones writes, is a standard that's comprehensive but tough to navigate:

"The odds of an organization accurately measuring and appropriately prioritizing its control improvements are extremely low."

So...Got a Smarter Way to Use the Framework?

In Part 4 of his blog series, Jack shows how the FAIR model could be applied to the NIST Framework to calculate an ROI on moving up the Tiers.

The first step is to create a loss event scenario—in Jack’s example, “sensitive data is accidentally disclosed to unauthorized persons when disk drives are taken out of service and inappropriately disposed of”.

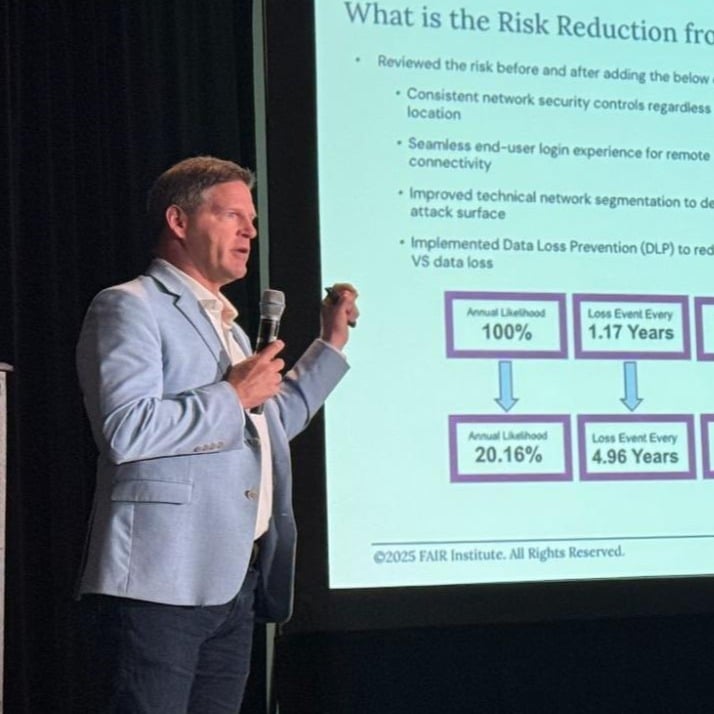

The next step: Estimating a range of improvements in number and magnitude of loss events as the company improves its controls (following the NIST CSF to-do lists). Then running the scenario through FAIR (as powered by the RiskLens application).

The result: A dollar value on the improvements and some meaningful guidance on how to choose among the 98 subcategories for action.

Will NIST Make the Framework More Useful for Business?

NIST is in the middle of a review heading toward a version 1.1 of CSF—and one of the hottest debates is around how to put inject some metrics into the Framework.

NIST has included a metrics proposal in the draft of 1.1 but, as FAIR analyst Chad Weinman points out in his CSF 1.1 evaluation, NIST's notion of mapping corporate KPI's (like systems uptime) to the Framework wouldn't be much guidance.

In comments filed for the review, FAIR Institute and the Internet Security Alliance (ISA) jointly proposed that “the cost effectiveness of the CSF needs to be demonstrated” to win wide acceptance by business and suggested that NIST look at integrating FAIR with the Framework, as many organizations are already doing in practice.

And in this post, Metrics? What Metrics? Finding the Missing Link to the NIST Cybersecurity Framework, ISA President/CEO Larry Clinton makes the case that the old thinking on NIST CSF needs to change. If metrics were developed, the thinking went, they would turn into fixed mandates that would inevitably be outgrown by the changing landscape of cyber threats.

In fact, says Clinton, “the constant and increasingly troubling drumbeat of cyberattacks combined with the inability to fulfill the requirements…that the CSF be cost effective and prioritized has created irresistible pressure toward developing metrics for the CSF”.

“By demonstrating a cost-effective process to enhance cybersecurity for the first time moves us firmly away from a 20th century compliance model and drives us toward a model based on actual security instead of compliance,” Clinton concludes.