In part 1 of this series, I said that quantification was the “easy” part of adopting a more mature approach to risk analysis, and that implementing organizational change was the hard part. In this post, I’ll share the most prominent obstacles I’ve witnessed regarding the process of change.

In part 1 of this series, I said that quantification was the “easy” part of adopting a more mature approach to risk analysis, and that implementing organizational change was the hard part. In this post, I’ll share the most prominent obstacles I’ve witnessed regarding the process of change.

The Main Obstacles

InertiaOrganizations and people tend to resist change. This can be especially true if:

- Current practices are widely accepted

- There are misconceptions regarding the difficulty/feasibility of the new practices

- Change requires different skills than are required

- Key stakeholders aren't actively calling for change

Unfortunately, all four of these conditions exist to some degree in the information security and operational risk landscape.

Current practices

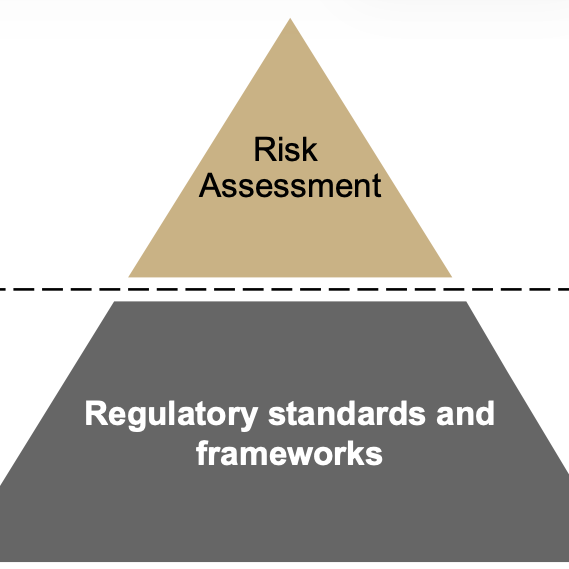

It is no secret that the information security profession has become highly reliant on "checklist risk management.” Whether it’s the FFIEC CAT, NIST CSF, PCI, ISO, BITS SIG or something homegrown, organizations focus heavily on compliance with one or more checklists as a way to determine if they are managing risk well. It's what many regulators and other stakeholders expect, and the serious limitations of checklist risk management aren't well understood or commonly discussed.

None of the common industry checklists I’m familiar with help with prioritization, at least in any meaningful way. You either are compliant with the checklist requirement, or not. How much you should care about a non-compliant condition isn’t part of the equation. This is actually a good thing, as the significance of a control state (whether compliant or not) has to be evaluated within the context of the assets at risk, the threat landscape, and other controls; which these checklists don’t take into account. Unfortunately, absent a formal risk analysis framework like FAIR, the significance of any non-compliant condition is established by the security or audit professional who, very often, simply waves a wet finger in the air.

Here again, I don’t want to be misunderstood. There isn’t anything wrong with waving wet fingers in the air when you don’t have the time or don't need to be more rigorous. The problem, however, is that wet finger waving is entirely reliant on the mental risk model of the person doing the waving. If that mental risk model is well calibrated, both in terms of completeness and ontological correctness (i.e., how the elements relate to one another), then the probability of an accurate estimate increases significantly. Much of what I see in practice though, suggests that well calibrated mental models are relatively few and far between, meaning that accurate analyses are a crapshoot. This is the second major value proposition of FAIR: that it helps to calibrate a professional’s mental model of risk. Even better, when the mental models for risk are consistent within an organization, analysis consistency and quality improves and unproductive debate decreases systemically.

Misconceptions

- They're simply parroting something they heard someone else say

- They have bought into common fallacies regarding risk quantification, for example:

- The need for high volumes of data

- The need for precise measurements

- The notion that pure objectivity is required (or even achievable)

A related fallacy is that, "Quantification takes too much time." Here again, a little probing finds the same unsubstantiated reasoning.

Regardless, these misconceptions can be terribly difficult to talk someone out of if they aren't open to being talked out of it.

Different skills

Doing "real" analysis (i.e., taking it beyond a wet finger in the air) requires skills that are not commonly exercised in today's checklist/wet finger risk management world. As a result, it can be difficult to find people who have the necessary:

- Critical thinking skills

- Comfort with numbers

- Understanding of basic concepts regarding probability

The good news is that people with these skills have a marvelous opportunity for growth in their career as risk practices continue to evolve.

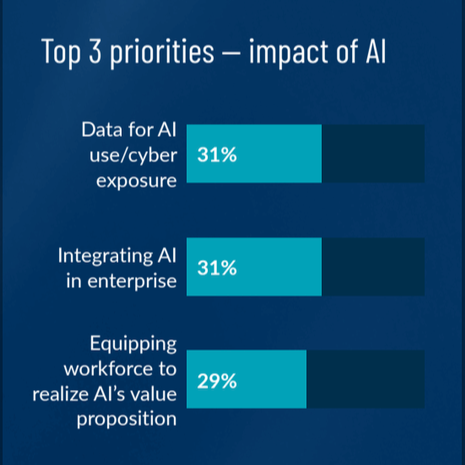

Key stakeholder expectations

Real, lasting change is only likely to occur if key stakeholders (e.g., the Board, C-level, external auditors, regulators, etc.) insist upon it or at least support it. Otherwise, the status quo will likely prevail. Unfortunately, to-date these people seem to have the perception that qualitative/ordinal scales and checklists are state-of-the-art. This is slowly beginning to change, but it still represents a significant obstacle for many organizations. This problem is exacerbated by continued advocacy of the checklist mentality by industry standards bodies.

One more (obstacle) for the road

If one person’s “risk” is another person’s “threat” and yet another person’s “vulnerability”, there’s very little hope that the complex risk landscape can be effectively and accurately measured quantitatively — or qualitatively, for that matter. Whether it’s in conversations, media articles, annual reports by major players in the information security industry, or in common standards that the industry relies upon, foundational terms are used imprecisely and inconsistently on a remarkable scale. This being the case, it’s of little surprise that quantitative risk measurement is considered infeasible. Some even claim it’s impossible.

Age-old wisdom states, “What gets measured, gets managed.” I’ll take it a step further though, and suggest, "You can only measure what you have clearly defined." That, in fact, is the first value proposition FAIR provides: clear definitions for the elements that make up the risk landscape. This is particularly powerful when those definitions are adopted organization-wide, which reduces confusion and facilitates more productive discussions on the topic of risk.

Until organizations resolve this issue, it’s roughly analogous to riding a space shuttle mission when the scientists and engineers who planned the mission and designed the spacecraft haven’t agreed on the definitions for mass, weight, and velocity.

In the next (and last) post of this series, I'll discuss some things that can help organizations overcome these obstacles.