IT Risk Management teams are increasingly looking for help with their Risk Control Self Assessment (RCSA) process, to make it more defensible, and in turn, more useful to their organizations through the implementation of FAIR concepts.

IT Risk Management teams are increasingly looking for help with their Risk Control Self Assessment (RCSA) process, to make it more defensible, and in turn, more useful to their organizations through the implementation of FAIR concepts.

For those unfamiliar with an RCSA, like other risk assessment processes out there, the process attempts to identify and assess organizational concerns, both from an inherent and residual risk perspective, leveraging ordinal scales. This approach is typically seen in the Banking and Finance sectors and is often times a coordinated effort stemming from an Operational or Enterprise Risk Management function and conducted at each line of business.

As someone who’s been on the client side, conducting RCSA’s for the IT/Information Security LOB for a financial institution, I know first-hand how flawed and inconsistent the process and results can be.

Below, I identify three of my biggest problems with the RCSA process, and how leveraging some simple FAIR concepts can lend tremendous credibility and defensibility to your next RCSA.

Scope: Define Your Risk Statement

The first fundamental flaw of the process is tied to how scenarios are framed for analysis, otherwise known as scope. The scope of an analysis is meant to give your audience a clear depiction of the problem you’re analyzing. If done right, consensus should be achieved among your peers, and provide them sufficient understanding to begin identifying appropriate frequencies of occurrence and orders of loss magnitude, to use the two key components of risks, according to FAIR. Needless to say, if done poorly, the opposite is true. High level, vague scenarios like “malware”, leaves too much to interpretation, leading to inaccurate and un-useful results.

This is the first place where FAIR can play a tremendous role. Even before quantifying anything, having a clear understanding of the risk scenario will shed a significant amount of light on the problem you are analyzing, and ensure everyone involved is on the same page. When conducting an analysis, we always look to identify:

- Asset: The focus, or item of value in an analysis that can be harmed (data types, people, processes, etc.)

- Threat: The acting force in an analysis that can cause harm (cyber criminals, insiders – malicious and error, natural disasters, etc.)

- Effect: The characteristic of the asset that the threat seeks to impact (Confidentiality, Integrity or Availability)

Tying these components all together into a risk statement, such as “the risk associated with malware infections leading to internal database breaches”, ensures everyone is on the same page.

Ordinal Scales: Tie Them to Frequencies & Magnitudes

The second area for improvement in RSCA is associated with the subjective and squishy ordinal scales used as proxies for frequency, or likelihood and impact. Most RCSA processes assess scenarios according to a 1 – 5 or 1 – 10 scale, and associate each with a description, “very likely”, “moderately likely”, “unlikely”, “high impact”, “medium impact”, you guessed it, “low impact”. As with any qualitative risk analysis, my interpretation of those terms will invariably be different than yours as we’ve had different experiences and most likely have different risk tolerances. As a result, your assessment will be very different than mine, which makes discussing, comparing and consistently developing these results in any defensible manner exceptionally difficult.

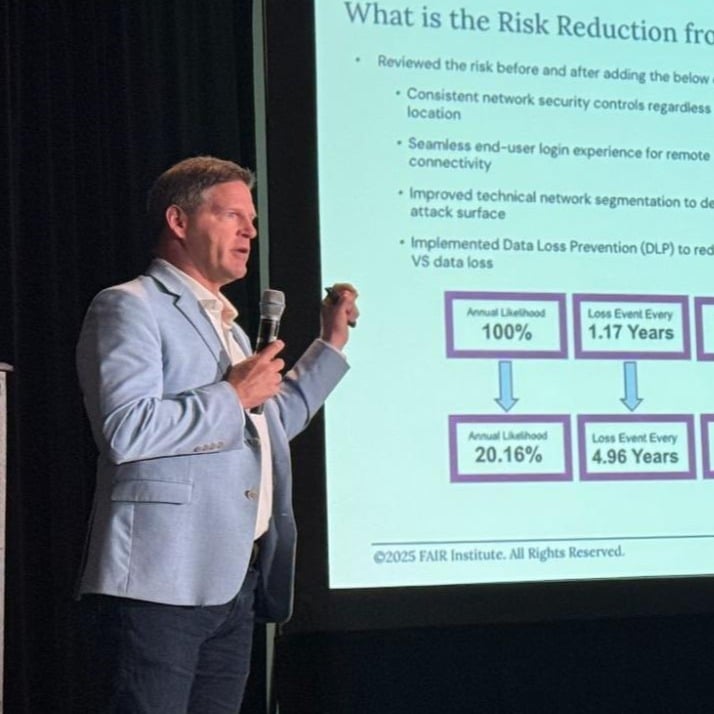

A big component of FAIR is reducing this level of ambiguity and inconsistent interpretation through the use of probability statements and dollars and cents. There is less room for interpretation with expressing results like a 10% probability of experiencing a $500,000 loss, than with expressing results as a moderately likely chance of experiencing a high impact.

To get to this point, a recommended initial step would be to tie actual frequencies, or probability statements and dollars and cents to the ordinal scales. This should immediately clarify what a risk assessed as “very likely” means, and whether or not all of your peers agree as well.

Question “Inherent Risk”

The last, and probably most aggravating issue I have with the RCSA process is the common definition of “inherent risk” as the absence of ALL controls. On so many levels, this doesn’t make sense and doesn’t seem useful for the purposes of conducting a risk assessment. If we wanted to assess the risk associated with external actors breaking into and stealing sensitive client data from a data center, would we peel away all controls and infrastructure until we got to a set of servers sitting in a corn field? With the above definition, this is where that conversation will lead you…I’ve been there.

FAIR’s role here is about providing a framework for critical thinking. Like any good model, FAIR breaks down our problem space and helps us better understand and communicate risk. With this level of clarity comes the confidence, and I’d dare say obligation to question things that don’t make sense or help us ultimately achieve our risk management goals. In this vein, does the removal of all controls help us understand our risk (i.e. the probable frequency and probable magnitude of future loss)? Does it help us make more well-informed risk decisions? I don’t think so. Don’t be afraid to ask questions.