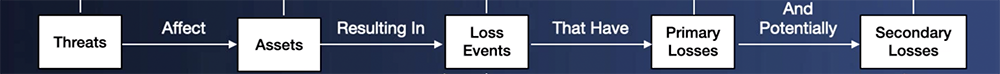

Factor Analysis of Information Risk (FAIR™) is referred to as the standard model for cyber risk quantification – and it is indeed that highly useful tool for analyzing risk in non-technical, business terms. But it’s also a set of key concepts that enable critical thinking about risk and business processes more generally - concepts that can be shared within an organization as a common point of reference for risk-based decision-making, starting with a foundational definition of risk as the “probable frequency and probable magnitude of future loss.”

FAIR creator Jack Jones crystalized these concepts in the FAIR book, Measuring and Managing Information Risk, Jack’s blog posts and many other writings and speeches. Here’s a sampling:

FAIR Quantitative Risk Analysis – Some Key Concepts

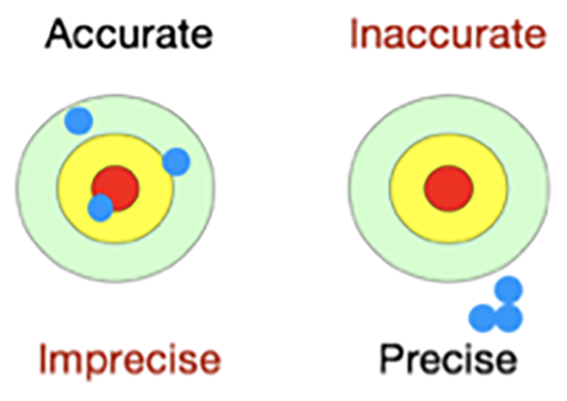

1. Accuracy over Precision

The results of FAIR analysis are always presented in ranges to account for the uncertainty of any risk measurement. The goal of risk measurement can only be a reduction in uncertainty. Remember, you’re not making a prediction, you’re assessing probable loss exposure. So, the goal is to be accurate within a range, with a useful degree of precision. As Jack writes:

For those who might be unclear about the distinction, you should think of precision as “exactness” and accuracy as “truthfulness.” You can have very exact answers that aren’t truthful, for example I could claim to be exactly 6’3” tall, but in fact I’m 5’9” tall, so my claim would be inaccurate. Alternatively, I could claim to be between 5’6” and 6’0” tall, which would be accurate, but not highly precise.

An important implication: You don’t need to amass a perfect pile of data to do useful analysis. You can “faithfully express the quality of data you’re operating from, and thus your uncertainty, by expressing your estimates using wider, flatter distributions as appropriate,” Jack writes.

2. Don’t Analyze till You Scope

“Too often, risk registers become a due diligence dumping ground for everything that turns up from audits, self-examinations, policy exceptions, etc.,” Jack writes. “But here’s the catch — none of those things are risks. None. Nada. Zip. They are conditions that contribute to risk.” Effective risk analysis starts with “a clear scope of what’s being measured — e.g., the asset(s) at risk, the relevant threat(s), the type of event (outage, data compromise, fraud, etc.).”

Examples of clearly scoped scenarios for risk analysis:

Analyze the risk associated with malicious privileged insiders inappropriately exfiltrating and sharing customer PII contained in the customer database, resulting in confidentiality loss.

Analyze the risk associated with non-malicious privileged insiders misdelivering emails containing sensitive customer information, resulting in confidentiality loss.

Not only does the scope clarify the analysis task at hand, it is the prerequisite for defensible quantitative (or qualitative) analysis – with an identified threat, asset and event, we can fill out the FAIR factors with values (#,%, $) for the probable frequency and impact of the scenario, based on data from the organization’s own cyber incident history and/or from standard industry data.

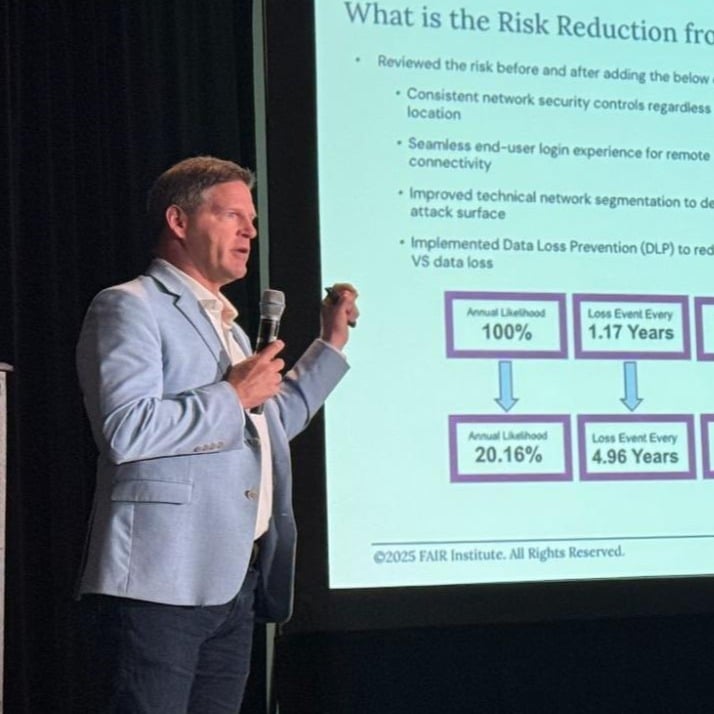

“If you can boil it down to the specific loss event scenarios that resonate with business leaders, they can understand the disruption of the critical service which is supporting their business goal,” said Drew Simonis, VP, Global Security, Hewlett Packard Enterprise, in a FAIR Institute “Meet a Member” interview.

3. Models Matter

Historically, cybersecurity has relied on qualitative risk measurements. However, as Jack points out:

When someone uses their gut/expertise to qualitatively rate something as high/medium/low risk, invariably they are using their own mental model of risk, plus whatever informal anecdotal data is stored in their memory. Not exactly a recipe for reliable measurement.

The Open Group, a global consortium of more than 500 technology organizations, established FAIR as the international standard for quantitative risk management after a rigorous review process, and the group continues to maintain and update the FAIR standard. Why does this matter? Jack writes:

Open standards for complex things like encryption exist for a reason; that reason being it’s very difficult to get it right, and very easy to get it very wrong. And unfortunately, because cybersecurity risk measurement is complex and nuanced, those who aren’t deeply familiar with all the different ways it can go wrong won’t be able to differentiate a reliable model from an unreliable one.

As Jack writes, anyone can generate numbers with an algorithm, but risk analysis models have to be transparent and understood so the results can be defended:

For years now a lot of organizations have used FAIR in one form or another to great advantage, in part because the community understands and trusts it.

Learn more about FAIR thinking and terminology in these blog posts:

FAIR Terminology 101 – Risk, Threat Event Frequency and Vulnerability

FAIR vs. Proprietary Cyber Risk Analysis Models: What’s the Difference? Jack Jones Explains

FAIR Beginner's Guide: What Do the Numbers Mean?